BURIED IN WOOLLEN

26 JULY 2021

This day in the archive: 26th July

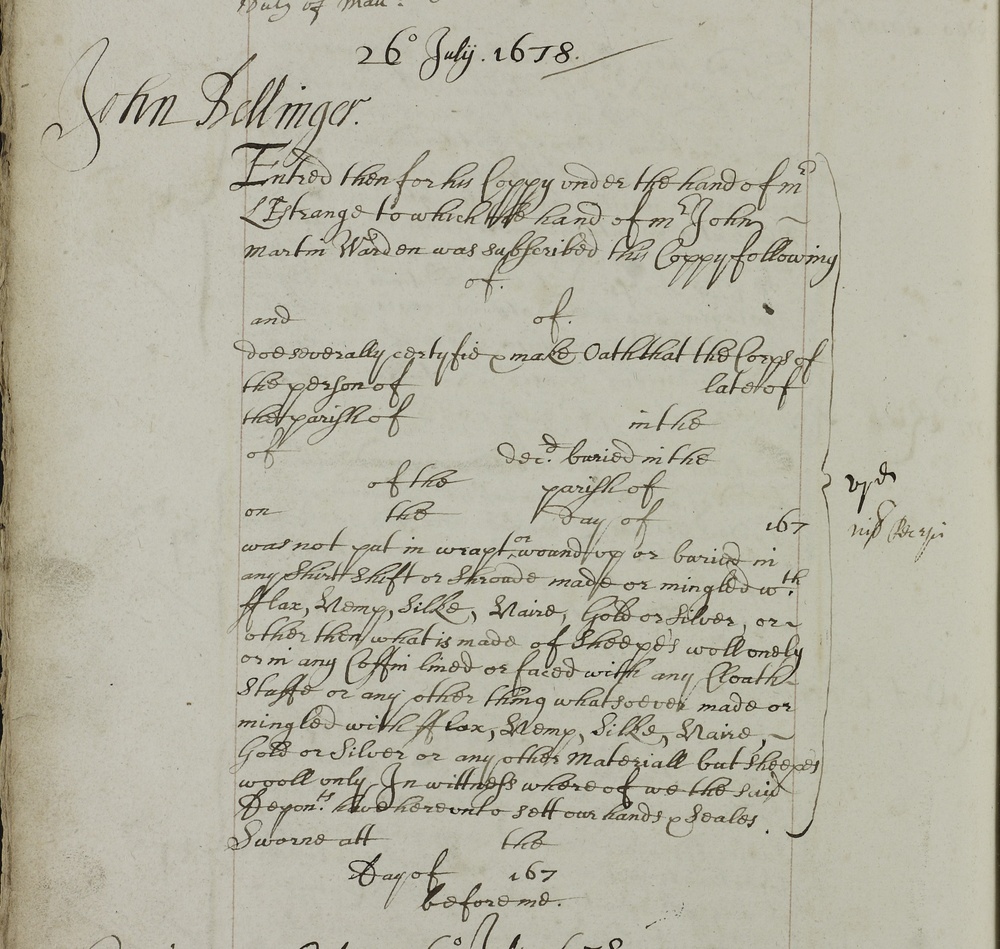

On 26th July 1678, an unusual entry was recorded in the Stationers' Register. It's the wording of an affidavit form, to be completed by two witnesses who 'doe severally certifie and make oath that the corps of the person of ... late of the parish of ... was not put in, wrapt or wound up or buried in any shirt, shift or shroude made or mingled with flax, hemp, silke, haire, gold or silver, or other then what is made of sheepe's woll onely.' The affidavit goes on to specify that the coffin must also be lined in wool.

Main image: Entry of copy for form of words of affidavit, 1678. Stationers' Company Archive, Liber F TSC/1/E/06/05

The first Act for burying in Woollen onely was passed in 1666. The wool trade had been central to the English economy since the Middle Ages: so much so, that in the fourteenth century, Edward III proclaimed that his Lord Chancellor should sit on a bale of wool, to symbolise the importance of this resource. This became the Woolsack, the traditional seat of the Lord Chancellor for several centuries. By the seventeenth century, however, domestic wool consumption was threatened by large-scale importation of linen. At a time when laundry was a laborious task, linen was far easier to wash than other available fabrics, including wool.

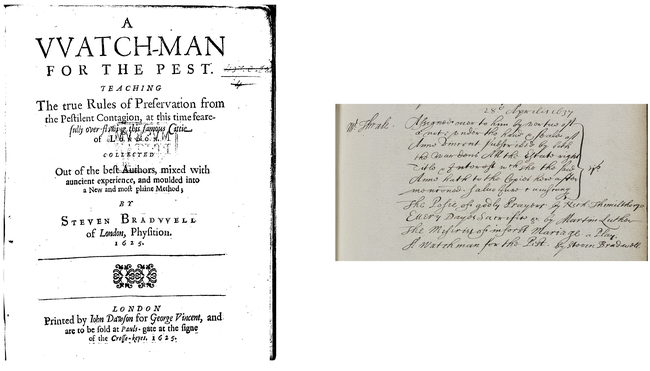

Thus, 'for the Encouragement of the Woollen Manufactures of this Kingdome', the 1666 Act specified that only wool must be used in burials, with the proviso that 'noe penaltie appointed by this Act shall be incurred for or by the reason of any person that shall dye of the Plague though such person be buryed in Linnen'. Outbreaks of bubonic plague were particularly severe during the seventeenth century, and there was a widespread (if mistaken) belief that 'Woolen cloaths will retaine the infection three or foure yeares, except they be well and throughly aired' (Stephen Bradwell, A Watchman for the Pest). Bradwell's 1625 tract was one of the many medical self-help guides published during the seventeenth century, and lapped up by a readership eager to protect themselves from a plague whose persistent recurrences continued to ravage the population.

Left: Title page of A Watchman for the Pest, 1625. Reproduction of the original in the British Library, downloaded from Historical Texts

Right: Reassignment of copy for A Watchman for the Pest, 1637. Stationers' Company Archive, Liber D TSC/1/E/06/03

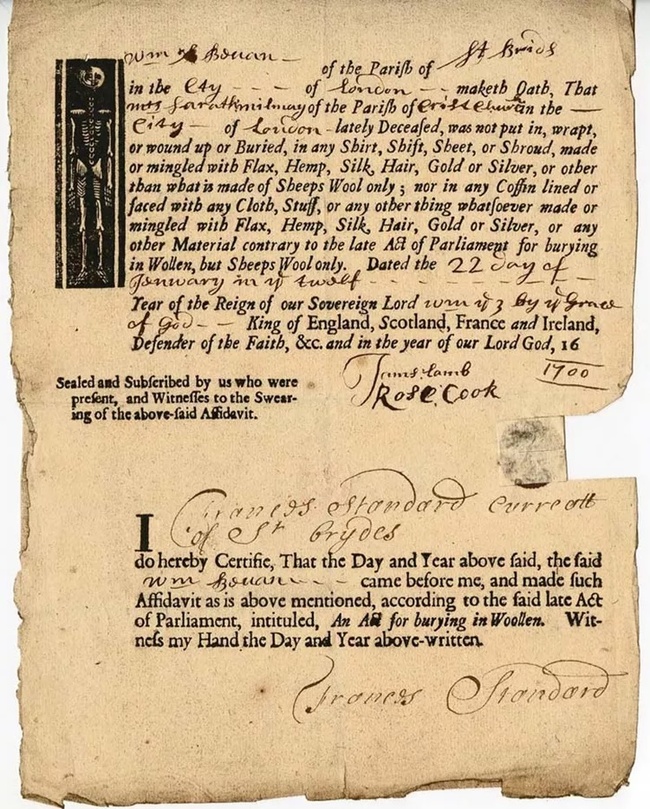

The 1666 Burying in Woollen Act does not appear to have been widely observed. A large proportion of burials would, of course, have been plague cases, and so exempt. But there was also strong resistance from the public. Woollen shrouds were far more expensive than linen; and besides, for a predominantly Christian population, Jesus's burial in linen, described in all four Gospels, gave it an extra legitimation. In 1677/8, the Act was reissued in a stronger form, with a fine of £5 (about £570 in today's money) for non-compliance. In addition, an affidavit attesting to the correct form of burial had to be sworn and signed in the presence of a clergyman, who was to keep a register of both burials and affidavits presented. Below is an example of a printed and completed affidavit form. This is the form for Sarah Mildmay, buried in the south transept of Westminster Abbey in 1700:

Mildmay burial affidavit, Image © Dean and Chapter of Westminster

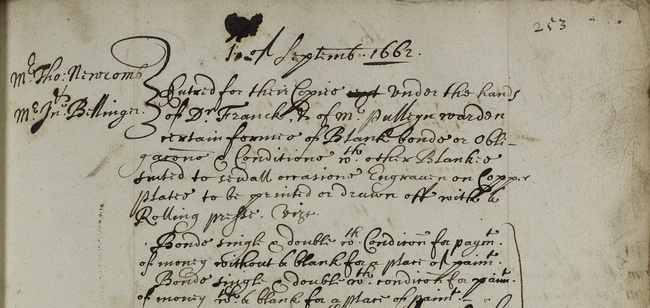

The Stationer entering the copy for the affidavit, John Bellinger, had an interesting career. The son of a girdler, he served his apprenticeship with Stationer Humphrey Tuckey, and was made a Freeman of the Company in 1650. Alongside a mixture of legal and historical texts, from 1658 he specialised in entering the copy for 'certain formes of blank bonds or Obligacons and Conditions with other Blankes suited to severall occasions, engraven on copper plates, to be printed or drawn off with a rolling presse,' as specified in one of these entries (below). These were generally variations of official IOUs.

Entry of copy for bonds, 1662. Stationers' Company Archive, Liber F TSC/1/E/06/05

Bellinger adapted this speciality to the requirements of the Crown: in 1673, he entered for his copy a 'Testimoniall or certificate of ye record to be made in the Quarter Sessions of the respective counties, citties, boroughs, and places within the realme of England, dominion of Whales and towne of Berwick uppon Tweede, and the islands of Jersey & Guernsey.' This attested that an individual had sworn the oaths of Supremacy and Allegiance demanded by the increasingly embattled Charles II. In 1678, as well as the affidavits for the 'burying in Woollen' Act, Bellinger registered a form to be completed by parish assessors to certify the level of poll tax payable by all parishioners, and a form to appoint poll-tax collectors, in order to fund a potential war against France.

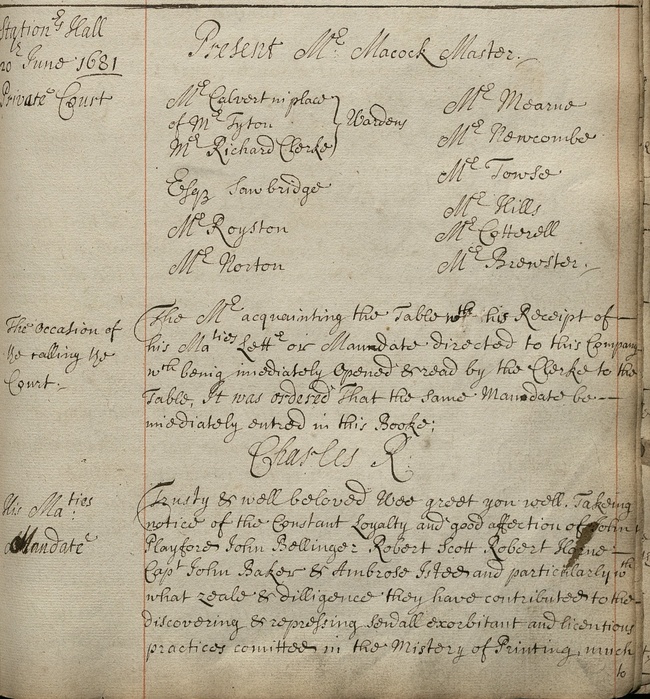

Bellinger succeeded in impressing Charles, and in 1681, when a special Court of the Stationers' Company was convened to discuss a memorandum from the King instructing them to appoint certain 'men of active loyalty and vigour' as Court Assistants, Bellinger's name was among those chosen. He was again favoured when Charles II issued the Company with its new Charter in 1684.

Bellinger appointed to the Court. Stationers' Company Archive, Court Book E TSC/1/B/01/03

Charles's interference with senior appointments was one of the most disliked aspects of his intervention in City Charters, and when William and Mary succeeded to the throne in 1688, the Charters were reissued in their original form. As a result, Bellinger was temporarily removed from the Court of the Stationers' Company, but, alongside Charles's other appointments, he was soon restored to his position, and remained on the Court until his death in 1695.

As for the 'burying in Woollen' Act, the 1678 reinforcements proved effective, and evidence suggests that linen imports fell over the next few decades. However, over the course of the eighteenth century, the wool industry lost its importance to the economy. The Industrial Revolution ushered in the mechanised production of cotton textiles, and the Wool Act was repealed in 1814. In a strange twist of fate, the growing popularity of environmentally sustainable and biodegradable coffins has seen a new interest in burial in wool.