ROMEO AND JULIET: A STATIONERS' COMPANY PRODUCTION

14 FEBRUARY 2023

This Valentine’s Day, we look at the Stationers behind the publication of one of the greatest love stories of all time: Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet.

Main image: Frontispiece of Giulietta e Romeo by Luigi da Porto, 1530. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

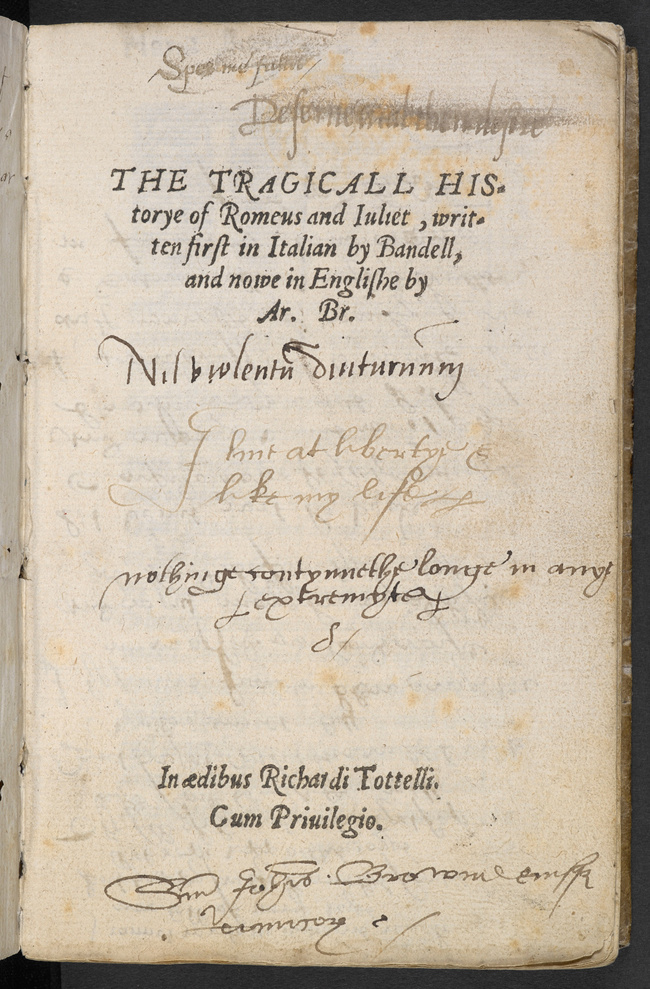

One of the key sources of Shakespeare’s play is a text called The Tragicall Historye of Romeus and Iuliet, translated from the Italian by Arthur Brooke and published by Richard Tottell in 1562.

Title page of Arthur Brooke's poem, Romeus and Juliet. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

This proved to be yet another canny investment for Tottell, one of the most prosperous Stationers of his day, who owned exclusive rights to print several key law texts. Brooke’s sympathetic portrayal of the lovers became hugely popular with its Elizabethan audience, running to several subsequent editions. Named in the Stationers’ original Charter of 1557, Tottell was generous in his contributions to the Company, and served as Master twice, in 1578–9 and 1584–5. His key contribution to literary history was his publication of Songes and Sonettes, a collection of early Tudor poetry. Better known today as Tottell’s Miscellany, the anthology popularised the sonnet as the poetic form which came to define the era.

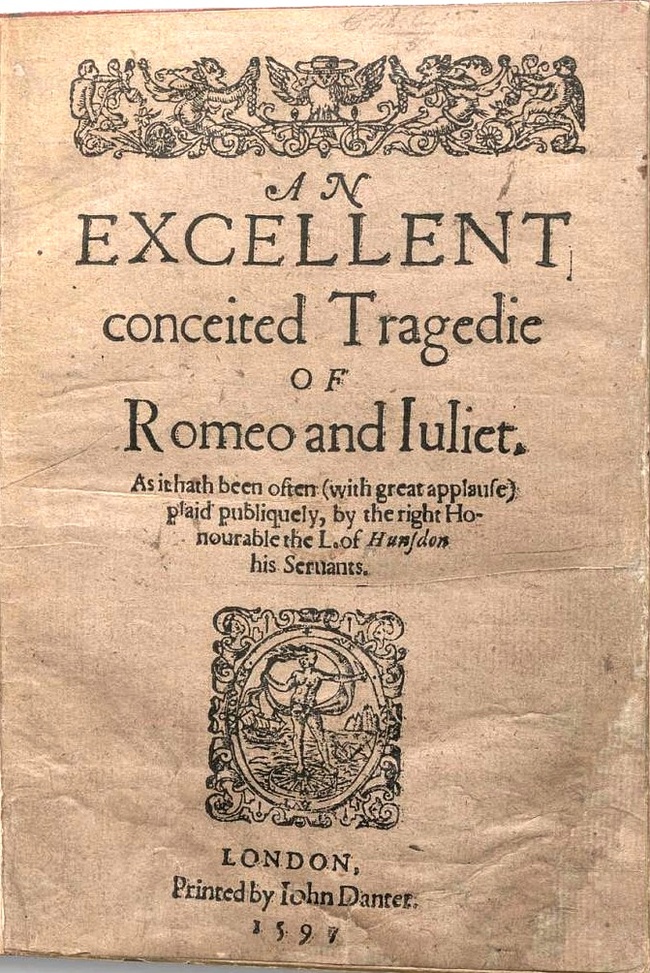

Title page of Romeo and Juliet, Q1. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Romeo and Juliet’s first appearance in print, in 1597, was an inauspicious one. Poorly printed, full of discrepancies, and unregistered, this version is generally referred to as a ‘bad quarto’, the name given to unauthorised play texts, possibly reconstructed from a few actors’ faulty memories. The printer, John Danter, was also a Stationer, but a considerably less successful businessman than Tottell. He ran into trouble early on: as an apprentice, the Wardens of the Stationers' Company banned him from ever becoming a master printer due to his involvement in print piracy.

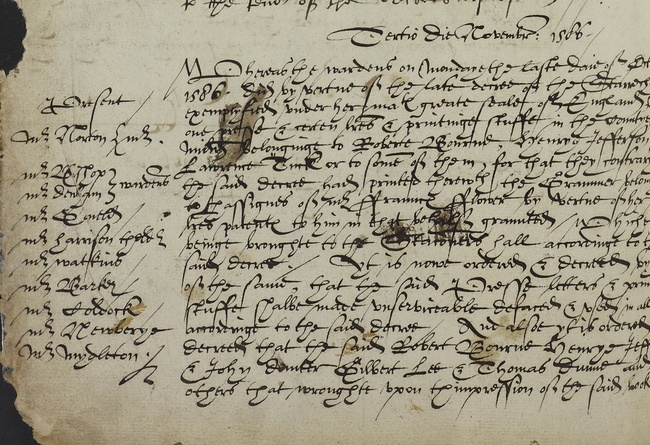

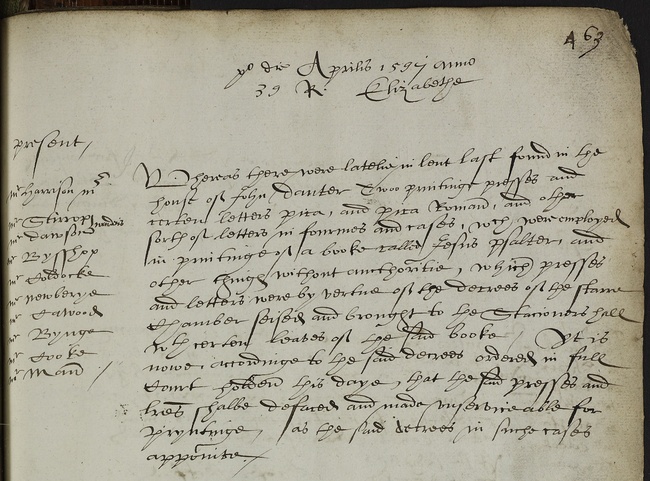

Left: Stationers' Company Court ruling barring John Danter, apprentice, from becoming a master printer, Liber B 3 November 1586; Right: Court order for the seizure and destruction of Danter's Press, Liber B 10 April 1597, Stationers' Company Archive, TSC/F/02/01

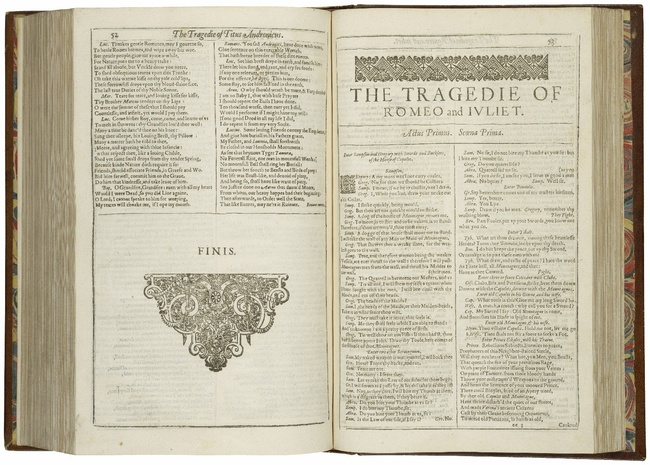

The sentence was revoked, and he worked through a period of relative stability, eventually setting up his own shop. He even became an early publisher of Shakespeare, registering and printing Titus Andronicus in 1594. But after his press was seized and destroyed in 1597 for printing a Catholic text, his fortunes took a turn for the worse. Soon after producing the pirated bad quarto of Romeo and Juliet, he again fell foul of the Stationers’ Company, this time (somewhat unsurprisingly) for printing books to which he had no title. He died not long after, impoverished and struggling with debt.

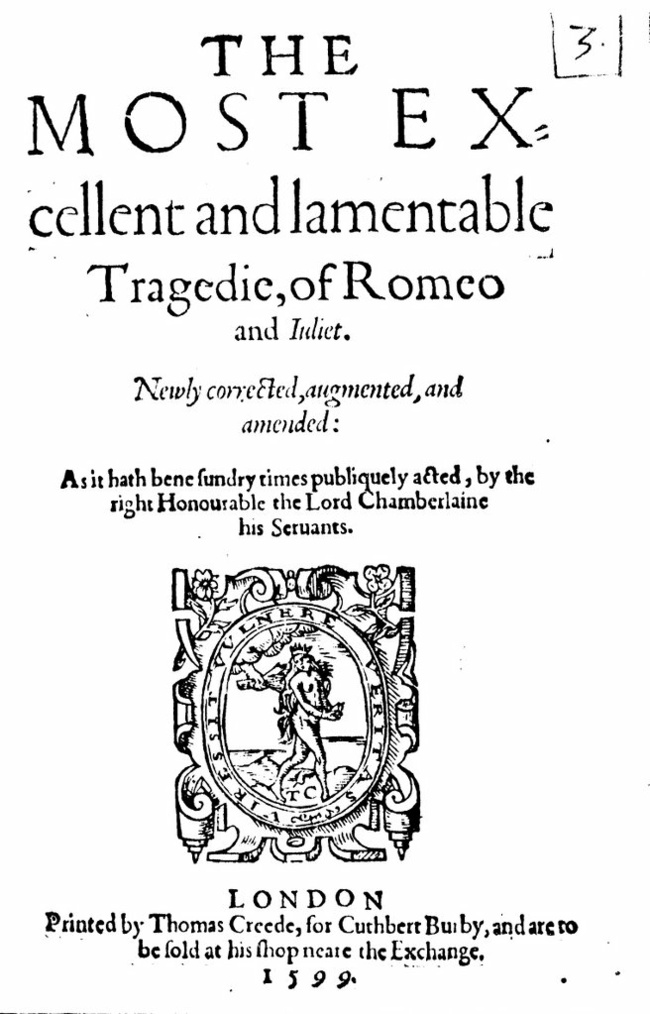

Title page of Romeo and Juliet, Q2. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Title page of Romeo and Juliet, Q2. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

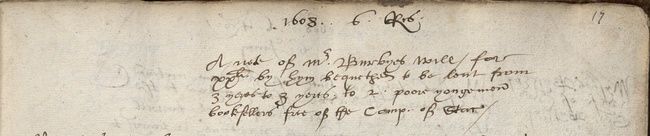

Shakespeare’s star-crossed lovers made a more successful foray into print in 1599, under the hands of Stationers Cuthbert Burby and Thomas Creede. Creede specialised in printing dramatic works, with Shakespeare, Marston, Dekker and Chapman among the playwrights he issued. He financed many of his earlier literary printing work himself, but by this point, he largely functioned as a trade printer, sharing jobs with other printers or printing work financed by other Stationers. In this case, the financing came from Burby, an affluent Liveryman who on his death bequeathed a sum of money to be lent to struggling young booksellers.

'1608: A note of Master Burbyes will for xx li [20 pounds] by hym bequethed to be lent from 3 yeres to 3 yeres to 2 poore yongemen bookesellers free of the Comp. of Stationers'. Stationers' Company Archive TSC/B/01/01

The second quarto printing of Romeo and Juliet was also unregistered (not required for a second printing), and is longer than Danter’s edition by some 800 lines. It has been suggested that the text was based on Shakespeare’s pre-performance draft – affectionately referred to by academics as his ‘foul papers’.

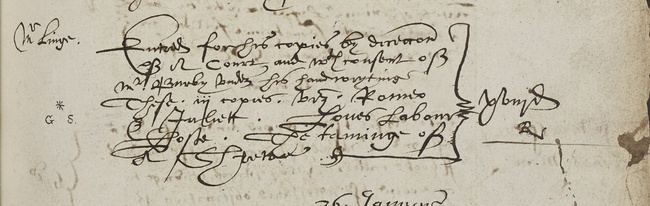

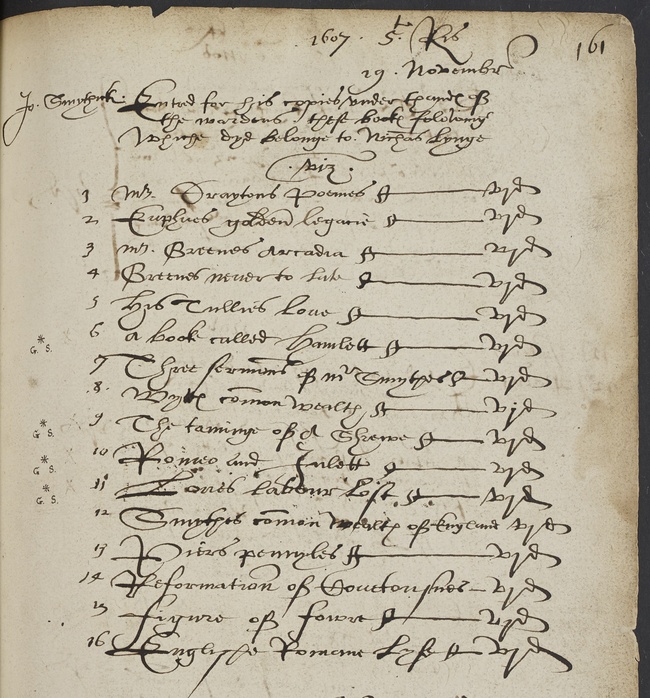

The play first entered the Stationers’ Register in 1607, when Burby transferred his right of copy to Nicholas Ling, along with two other plays, Love’s Labour Lost and The Taming of A Shrew.

Left: Entry of copy for Nicholas Ling, 22 January 1607. Right: Entry of copy for John Smethwick, 29 November 1607. Stationers' Company Archive, TSC/E/06/02

Ling did not have time to enjoy the rights: although his probate wasn’t pronounced in 1610, the bulk reassignment of his titles to John Smethwick in November 1607, together with his subsequent absence from the records, suggests that he died around then. A bookseller by trade, Smethwick cut an interesting figure among the Stationers: after launching his career with several fines for misdemeanours including the sale of privileged books, he proceeded to rise through the ranks of the Company, becoming Master in 1639. For a while he worked in partnership with John Jaggard, brother of William and uncle of Isaac, and it's perhaps not surprising that he was a shareholder in the publication of Shakespeare’s First Folio. Smethwick’s first publication of Romeo and Juliet was the quarto edition of 1609. Substantially the text which has enthralled readers and audiences ever since, its progress through print offers us a fascinating glimpse into working lives behind the scenes.

The title page from the First Folio, printed in 1623. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons