SURVIVING THE PLAGUE

17 APRIL 2020

Unsurprisingly, there have been a lot of references to ‘the plague’ in the media over the last few weeks. The 400-year pandemic of bubonic plague which swept from China into Europe in the fourteenth century is, in the popular imagination, the closest parallel we have to our current situation. Lately, when answering research queries, writing ‘Archive News’ posts, or looking up references for the Master’s letter, I’ve found myself consulting our digital Archive to understand how Stationers responded to outbreaks of plague in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. With limited medical understanding, restricted communication technologies, and inadequate social welfare, their predicament must have seemed far more terrifying and isolating than our own.

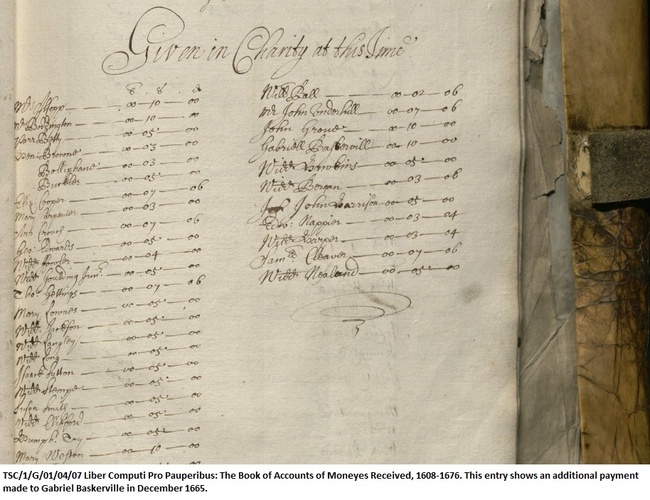

‘Visitations’ of disease are frequently mentioned in the Court records of the Stationers’ Company, most often via the restrictions on public gatherings and dinners noted in the latest edition of Stationers’ News, and in the Master’s letter to the Company. There are also references to charity, and one which particularly intrigued me, and which was quoted by the Master, dates from the epidemic which started in 1665, and became known as the Great Plague. An entry from Court Book D, for 26 September 1665, notes that the Court ‘ordered that ten shillings be given to Mr Bascavill, five shillings to Fawcett, and two shillings sixpence to Mrs Alsopp which said several sums Mr Sawbridge is desired to disburse, and likewise such other small sums to the poor from time to time (during this time of infection) as shall be thought fit, the whole sum not exceeding fifty shillings.’

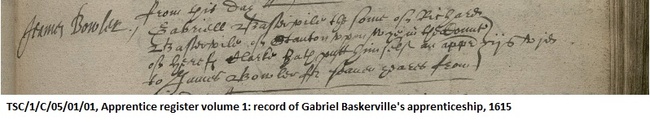

‘Mr Bascavill’ probably refers to Gabriel Baskerville, a Stationer with several appearances in the Company’s Liber Computi Pro Pauperibus (‘Poor Book’). No relation to the famous eighteenth-century typefounder, Gabriel Baskerville travelled from his home in Staunton-on-Wye, Herefordshire, in 1615, to take up an apprenticeship with London Stationer James Boler.

He gained his freedom in 1622, and as far as we know traded with reasonable success, taking on apprentices from 1626 onwards. The Poor Book records a one-off payment to him in 1647, and then, from December 1664, he received a regular pension. The fact that the Court records show a subsidiary payment to him in 1665 indicates the extra burden placed on the poor during the epidemic. Baskerville himself is unlikely to have been infected, as his pension payments continued until 1668, at which point they were transferred to his widow.

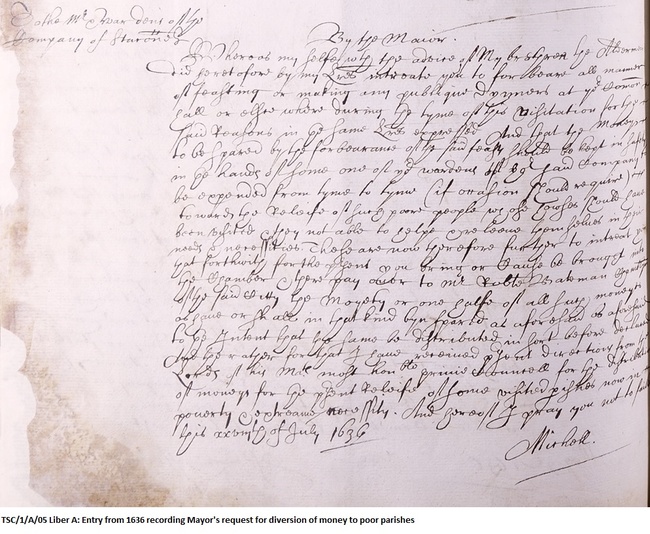

The payments recorded in the Poor Book came from the profits of the English Stock, and as such, their amount and regularity varied in accordance with the Stock’s fortunes. Originally paid quarterly, by the mid-1660s pensions were only distributed in June and December – hence the subsidiary September payment is noted in the Court records for 1665. Livery Companies played a crucial role in providing for the poor during the seventeenth century. Although principally charged with looking after their own members, this charity could extend to relieving parish burdens. In 1636, a particularly severe epidemic prompted the Lord Mayor of London to modify his prohibition on Livery Company dinners with a request that half the money saved from feasting, rather than being kept for the poor of the Company, should be handed over to the City Chamberlain, Robert Bateman, under ‘directions from the Lords of his Majesty’s most honourable Privy Council for the distribution of moneys for the present relief of some visited parishes now in poverty and extreme necessity’.

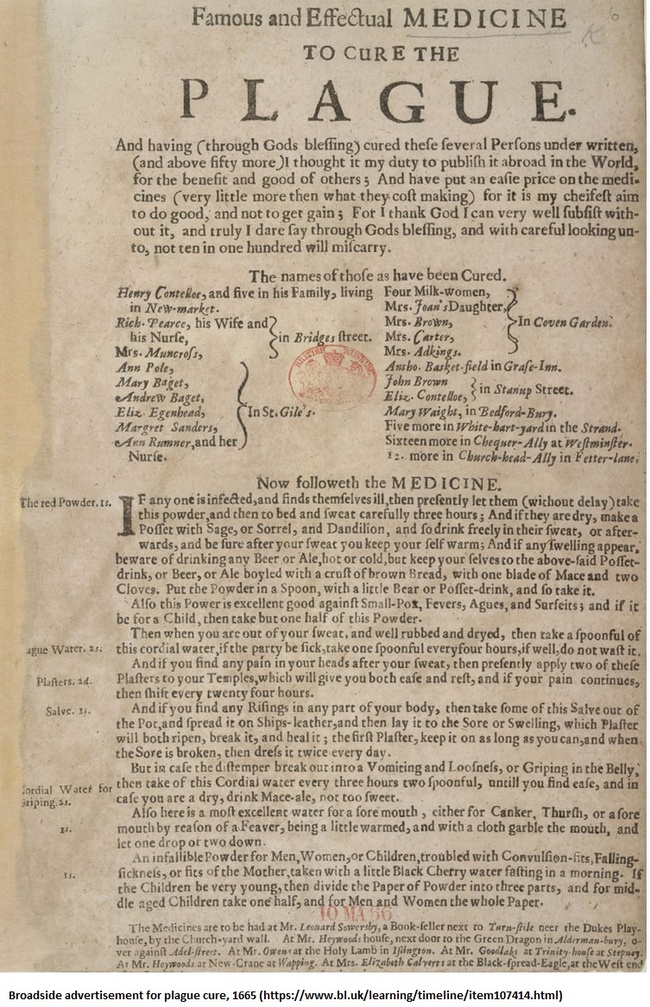

London poverty inevitably worsened in times of epidemic, when many businesses were forced to close, and their wealthier patrons often fled for the allegedly healthier air of the country. By the mid-seventeenth century, London was dangerously overcrowded, and poorer neighbourhoods, with their timber constructions and open sewers, offered plague-carrying rats the perfect breeding ground. An illness which was poorly understood, and stubbornly resistant to available treatments, easily lent itself to superstitious beliefs. As qualified physicians joined the exodus of the wealthy, the void in medical care was filled by quacks peddling ‘miracle’ cures.

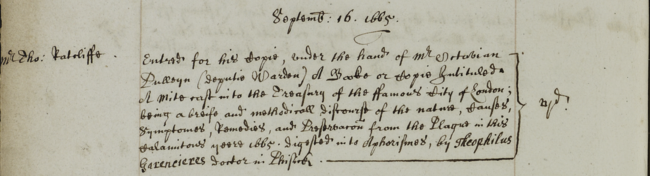

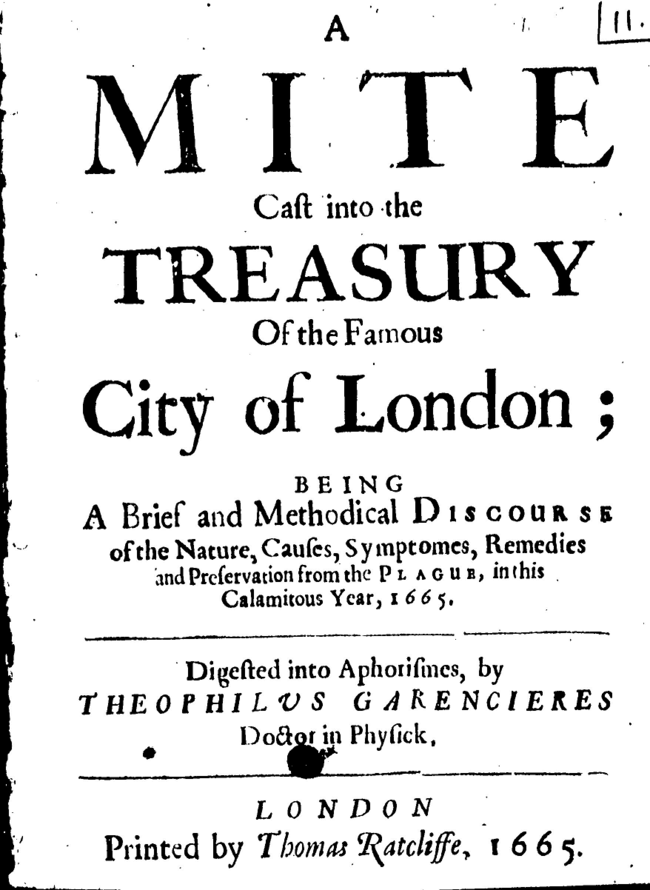

And even reputable doctors, subject (as we all are) to the limitations of their times, used a discourse of illness which today sounds both moralistic and alarmingly unscientific. Cheaper print and higher levels of literacy during the seventeenth century saw an increase in the publication of popular medical tracts and healthcare manuals, some of which were registered at Stationers’ Hall. Entered into the Stationers’ Register on 16th September 1665 is a work by one Theophilus Garencières entitled A Mite Cast Into the Treasury of the Famous City of London.

Garencières was a fully qualified doctor, trained in Caen and subsequently accredited in Oxford, having fled to England to escape religious persecution in France. As an associate of the College of Physicians in London, he belonged to the most highly educated echelons of his profession. A Mite Cast Into the Treasury continually refers to God’s judgement, and to the alignment of the stars. Astrology was a recognised factor in medical practice in those times, and Garencières was an avid reader of the prophecies of Nostradamus. Like many of his contemporaries, he regarded sightings of a comet in 1664 as a portent of the Great Plague.

Garencières’s observations of the causes of mortality from the plague provide a fascinating insight into conditions at the time (and into distinctions between medical practitioners):

'The causes why so few escape are these. The scarcity of able Physicians willing to attend that disease, the Inefficacy of common remedies, the want of accommodation, as cloaths, fire, room, dyet, attendants, the wilfullnesse of the patient, his poverty, his neglecting the first invasion, and trifling away the time till it be too late; a vapouring Chymist with his drops, an ignorant Apothecary with his blistering plasters, a wilfull Surgeon, an impudent Mountebanke, an intruding Gossip, and a carelesse Nurse.'

Garencières’s own recommended treatment sounds no more reassuring than the remedies peddled by ‘impudent Mountebanks’. It chiefly consists of force-feeding the patient a cordial composed of Venice treacle, tempered with cypress root, angelica, saffron, and some other plant-based ingredients. Venice treacle was a common name for theriac, a concoction of herbs and powdered viper flesh recommended by Galen in the second century AD. However, Garencières was no doubt quite sincere in his intentions, expressed in his dedication of A Mite Cast Into the Treasury to London’s Lord Mayor, ‘to give some few, short and perspicuous rules, whereby every one may know how to cure himself, and his family with a small charge.'

Researching the fortunes of the Stationers’ Company in plague time has been fascinating. And it’s certainly reminded me how lucky we are to be facing the current situation with the benefit of good sanitation, Netflix and the NHS. But now I feel it’s time to start investigating some of the other treasures of the Archive – limited as I am, for now, to the digital surrogates, which have really come into their own in this time of lockdown. I look forward to sharing my discoveries with you in forthcoming posts on Archive News.