THE STATIONERS' COMPANY CHARTER

9 JUNE 2021

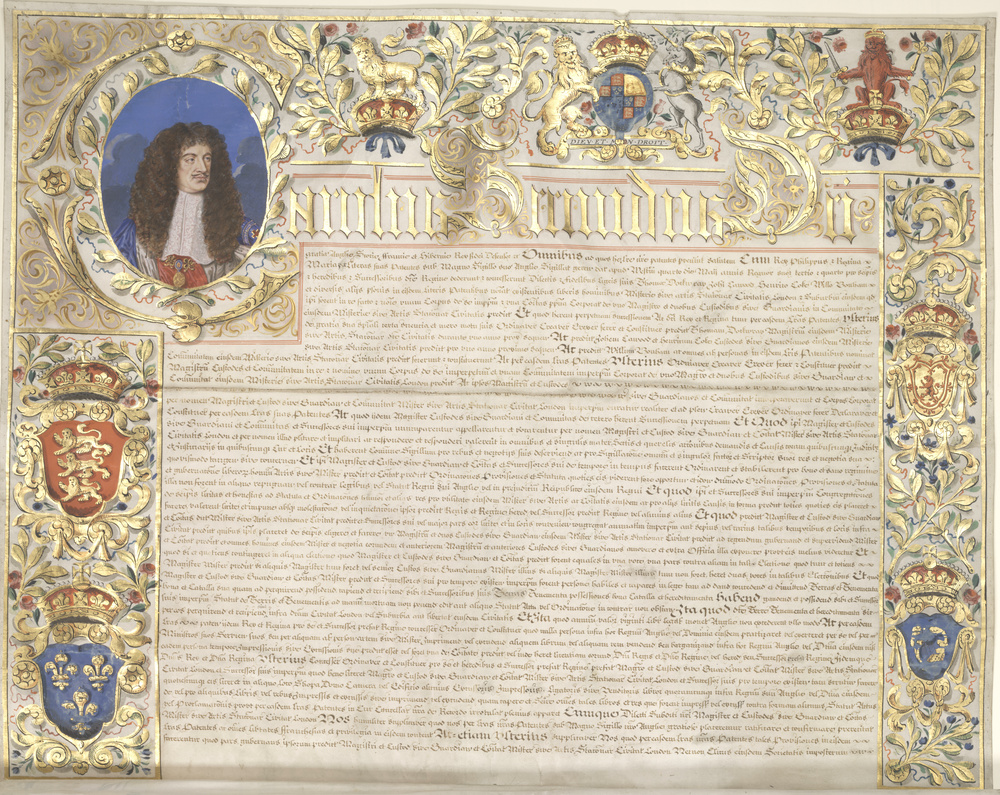

We're looking forward to our forthcoming Charter Dinner, celebrating the grant of a Royal Charter to the Stationers' Company in 1557. The original Charter was lost, probably in the 1666 Fire of London, but you'll all be familiar with the rather splendid 1684 Charter granted by Charles II in 1684, a facsimile of which hangs in the Court Room. Here I'm going to look at the story of political intrigue and manipulation behind that Charter - and what happened next...

First, let's remember why the Charter was important to the Stationers in the first place. Back in the sixteenth century, it was the final step towards incorporation, which allowed the Company to act as a collective legal entity. Following incorporation, the Company as a unit could enter and contest contracts, own land, and acquire printing privileges. Moreover, these privileges outlived the individual members of the Company. Incorporation was the first milestone on the Company's ascent to real power in the publishing world.

The Stationers managed to retain their power through the various political upheavals of what proved to be a turbulent century in English history. Religious sects were birthed into a dizzying cyle of suffering and inflicting persecution. Royal lines flourished and dwindled. Powerful people lost and recovered wealth and influence, and on occasion lost their heads (from which there was no recovery). However, it wasn't until the apparent restoration of stability - or, at least, of the monarchy - that the Stationers' Company charter was called into question.

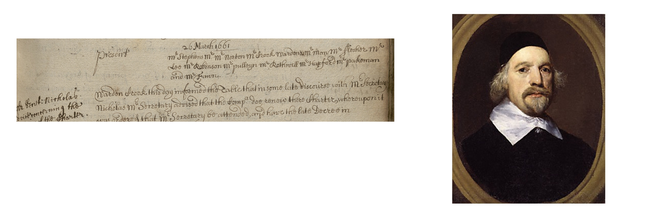

In 1661, as part of the Restoration Settlement, the reconstituted Parliament passed the Corporation Act, designed to remove from office any town official suspected of disloyalty to the Crown. In fact, Charles II had good reason to be suspicious: during the Civil War, the City of London's sympathies clearly lay with Parliament. The Stationers’ Company Court Book for 26 March 1661 records that ‘in some late discourse with Master Secretary Nicholas, Master Secretary advised that the Company do renew their charter.’ The Nicholas in question was Sir Edward Nicholas, one of the King’s most loyal advisers, who had also served as Secretary of State to Charles I.

Left: Entry for 26 March, 1661. Stationers' Company Archive TSC/1/B/01/02, Court Book D 1655-1579

Right: Sir Edward Nicholas (1593-1669) by William Dobson, c. 1645. © National Portrait Gallery, London

Politics during the Restoration was no more predictable than in the decades that preceded it, however, and Nicholas himself was unable to retain his post for long. But his advice to the Stationers’ was well judged. A later record from March 1665 sees the Court requesting ‘that a note of the date of the Charter of the Corporation, as also a copy of the subscription in the same, be taken out and delivered to Master Ratcliffe, who is desired to prevail so far with Master Prynne, as to make some search in the Tower for the Record of the said Charter and to take out a copy of the same.’

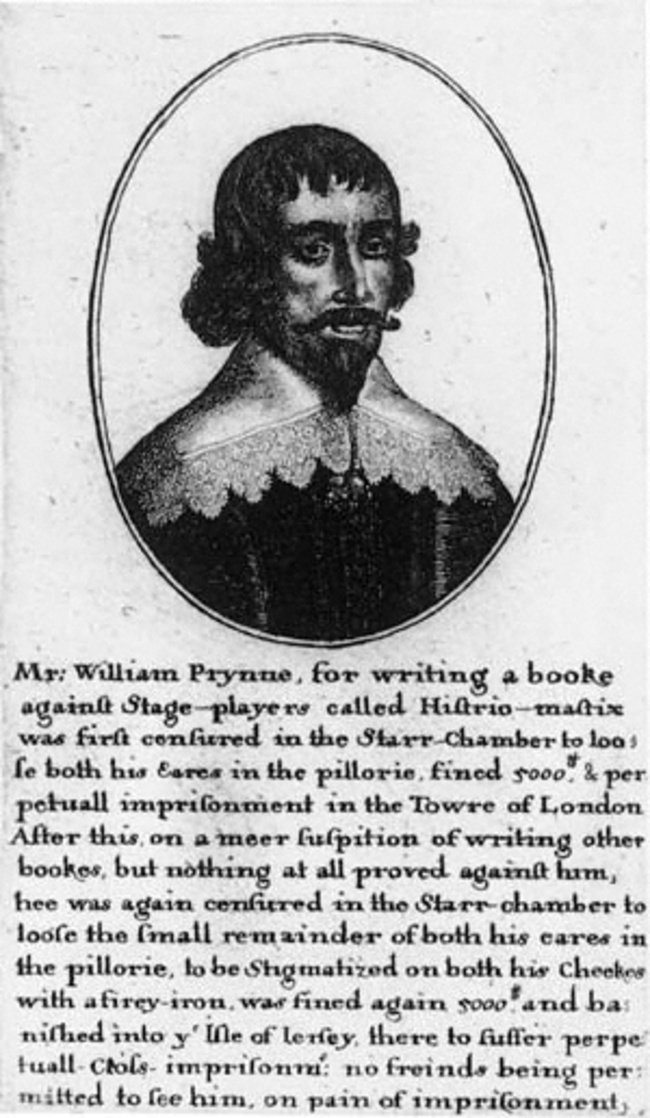

Portrait of William Prynne by Wenceslaus Hollar © National Portrait Gallery, London

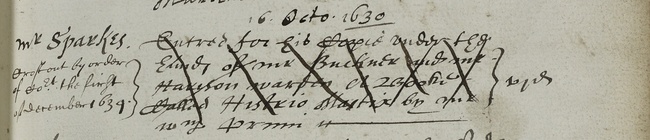

William Prynne was Keeper of the Records in the Tower of London, and had followed a strange trajectory to reach this position. A lawyer and prolific pamphleteer, under the reign of Charles I he fell foul of Star Chamber, with severe consequences. This is the entry of copy for Prynne’s 1630 work Histrio Mastix, a treatise against the theatre with particularly harsh words for female actors:

Stationers' Company Archive, Entry Book of Copies Liber D, 1620-1645, TSC/1/E/06/03

The pamphlet was not actually printed until 1633. The timing was unfortunate: Charles I’s consort, Queen Henrietta Maria, was just then rehearsing her role in a new pastoral comedy, The Shepherd’s Paradise by Walter Montagu. As you can see, the entry was crossed out in 1634, by order of the Court of the Stationers’ Company. Prynne himself was punished by the Crown with imprisonment and the pillory. An act of judicial mercy saw his ears merely cropped rather than completely amputated (a subsequent charge of seditious pamphleteering saw him more severely mutilated in 1637). Yet reversals of fortune were so rapid and dramatic during the tumultuous seventeenth century that, upon the Restoration of the monarchy, Charles II recognised Prynne’s long-term contributions to the Royalist cause by appointing Prynne Keeper of the Records.

The Stationers obtained their certified copies, but in the 1680s Charles II enforced a policy of seizing and regranting borough charters, which extended to the London livery companies.

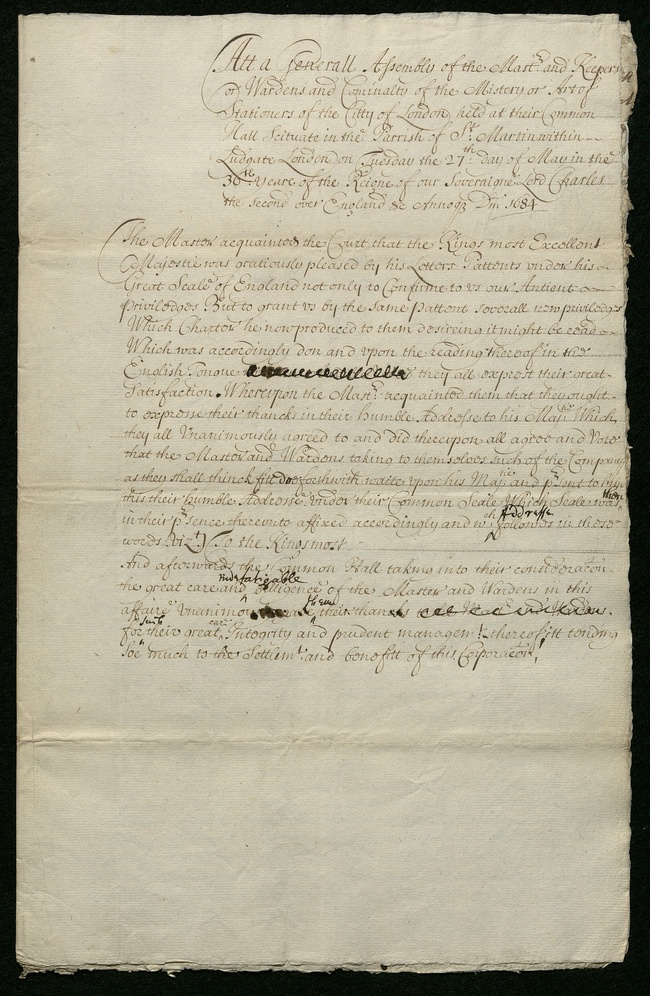

Entry in the rough court minutes for 27 May 1684 acknowledging Charles II's grant of a new charter. Stationers Archive TSC/1/B/03/03

The reissued charters gave the king power over the appointment of senior corporation officials. An ornate document whose lavish illustrations are typical of the period, this reissued Charter at least offers a decorative addition to the Court Room's walls (a facsimile, that is: the original remains safe in the Archive).

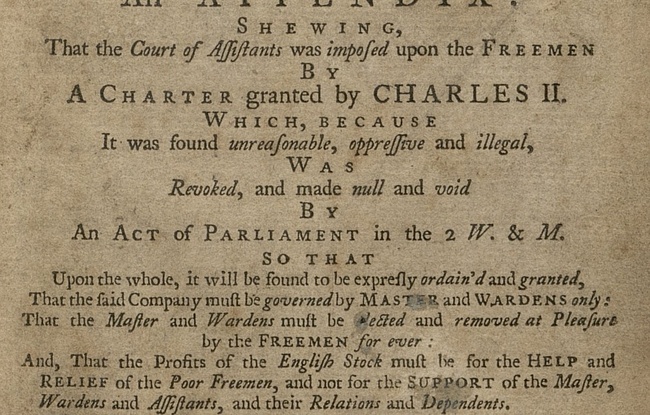

In fact, this Charter was to be short-lived. The 'Glorious Revolution' of 1688 saw yet another shake-up. William of Orange was popularly hailed as an antidote to the Stuarts' autocratic leanings. On their ascent to power, William and Mary revoked the Charters issued by Charles II, and reissued them in their original form. The commentary on the frontispiece of a 1741 printing of the Stationers' Charter spells it out: Charles II's Charter went down in history as the oppressive interference of a tyrannical monarch, happily superseded.